|

Too close for comfort

Former thrill seeker works to keep public at bay

By MARK MATTHEWS

Pictures by Chuck Bartlebaugh

When the woman noticed Bartlebaugh and his camera she asked him if he would take another shot with her standing by the elk as she smiled toward the camera. When the woman noticed Bartlebaugh and his camera she asked him if he would take another shot with her standing by the elk as she smiled toward the camera.

“I can’t encourage you to do that,” Bartlebaugh answered.

“Why not?” the woman asked.

“Because I’m trying to get a photograph of someone being gored by an elk.”

The outraged woman reported Bartlebaugh to the park authorities, but they were already well familiar with his work.

“Chuck helps us out a lot developing brochures that educate people about wildlife,” said Kerry Gunther, a bear management specialist at Yellowstone.

|

|

|

A bull elk appears to be oblivious to a child in Yellowstone Park, but that could change quickly, with tragic results for both the girl and the elk.

|

|

Bartlebaugh is the founding father and director of the Center for Wildlife Information, based in Missoula. According to the center’s literature, its goal is to “inform the next generation about how to safely and responsibly enjoy our wildlife and wild land treasures, especially bears.”

But Bartlebaugh wasn’t always such a conscientious conservationist. Up until the late-1970’s, he raced Indy cars on tracks throughout the country. After he retired he searched for an occupation that would be as stimulating.

“Without the risk-taking activity for two years, I was going bonkers,” he said.

With no experience either in wildlife biology or with focusing a camera, Bartlebaugh decided to become a professional grizzly bear photographer.

“I bought some gear, dressed up in an Eddie Bauer outfit, and headed to Yellowstone,” he said.

Before he got himself into too much trouble, a bartender at Cooke City set him straight.

“The last thing we need is another (expletive) with a camera getting killed,” he said.

Rather than run him out of town, the bartender introduced Bartlebaugh to the local forest ranger who took him under his wing. The first thing he had Bartlebaugh do was to change into blue jeans. Then he took him into the backcountry to teach him about bears, but without the camera.

“I didn’t understand where I was coming from at the time,” Bartlebaugh said. “It was all self-centered ego. I had no interest in the bear other than that the animal would get my attention.”

|

|

|

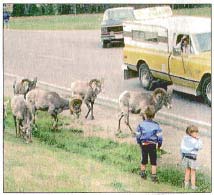

Bighorn sheep react nervously to two children in their midst.

|

|

Eighteen years later Bartlebaugh is educating photographers and tourists alike on how to interact with animals in a way that will protect themselves, as well as the critters.

“I’m sure the elk (that the woman posed next to) never even saw her,” Bartlebaugh said. “If it had looked up it might have reacted by running her over. And some people would have blamed the animal for simply trying to get away.

“We are training animals to do inappropriate things in our presence.”

Up to $100 million dollars a year is spent on misinformation about wildlife through the media, Bartlebaugh says. That includes television programs and wildlife documentaries, magazine and newspaper ads, and even news stories.

For instance, in late-July, NBC’s “Dateline Sunday” featured the story of Timothy Treadwell, a Californian who camps amidst the Alaskan brown bears during the summer and Katmai National Park near King Salmon, Alaska.

Treadwell photographs and videotapes animals, often with himself prominently exposed in the frame. At times he tries to get close enough to touch the 800-pound bears. He sings to them and whispers “I love you” in a soft voice when they come close.

Treadwell’s spiel is that the bears are not the evil killing machines that some people dread. His assessment may be correct, but Treadwell is not helping the bears with his antics, Bartlebaugh says.

“He’s potentially killing those bears by habituating them to humans,” he said. “He’s doing the most severe damage anyone can do.”

Bartlebaugh claims Treadwell is also spreading misinformation, especially when he compares the brown bear to Montana’s grizzlies.

For one, the Alaska brown bear, although the same species and genus, lives in an environment with a larger food supply. They are more likely to become habituated to humans who also visit their fishing spots.

On the other hand, Montana’s grizzly bears are solitary wanders who stake out up to 100-square miles of territory to meet their needs. Most avoid humans like the plague.

During the “Dateline” show Treadwell also said the bear population is up this year because of a wet spring that stimulated more vegetation.

“Bear populations just don’t jump up overnight with one wet spring,” Bartlebaugh said.

Treadwell’s behavior had spurred administrators at Katmai to get regulations in place that would require humans to stay at least 100 yards from bears, says spokeswoman Karen Gusten. “The last thing we want is to have a bear get used to human presence,” she said.

The Center for Wildlife Information will soon be printing the park’s first newsletter, much of which will be devoted to visitor safety issues concerning wildlife.

Bartlebaugh also works closely with other national parks to promote safe wildlife observation habits.

“Animals have an individual space, just like humans,” said Yellowstone’s Gunther. “If you get within that space, you get hurt.”

|

|

|

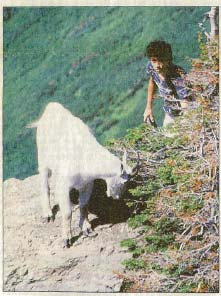

A mountain goat turns on a teenager who got too close in Glacier National Park.

|

|

This year bison have gored three tourists at Yellowstone and rolled another. “These people probably wouldn’t dare approach a big dog in the city, but when they come here they don’t think anything of walking up to a 2,000-pound bison,” Gunther said.

Wildlife photographers exhibit some of the most detrimental behavior towards animals, Bartlebaugh says. For instance, photographer Daniel Cox once bragged to a newspaper reporter that he uses only 200 millimeter lenses for most wildlife shots.

“The closer the better through,” he told the newspaper.

It’s the same attitude Bartlebaugh arrived with in Montana before he realized that animals that become habituated to humans change the behavior and stop exhibiting warning signs until it’s often too late for a person to avoid a disaster.

When a deer flicks its tail or a bison paws the ground, it is sign of stress and people should quickly back off, Bartlebaugh says. But animals get too used to humans, they may not give the sign until a person is right next to them. Then a quick jump or head butt could be lethal.

Bartlebaugh points out that deer kill more humans every year then grizzly bears do.

“People are expecting to interact with wildlife,” he said. They think the value of wildlife is to entertain.

“We can set aside acre after acre of habitat for grizzlies, but if someone walks in there with a cookie that draws the bear out, we’ve lost a lot.”

Reprinted by Center for Wildlife Information with permission from The Great Falls Tribune and the author.

|